Our First Packer Ancestor to come to the New World

Terry Packer is our guest blogger for a series of five posts telling the story about the research and acquisition of an early land transfer document signed by his ancestor.

Part 3 - 17TH CENTURY SPELLING AND PHRASES

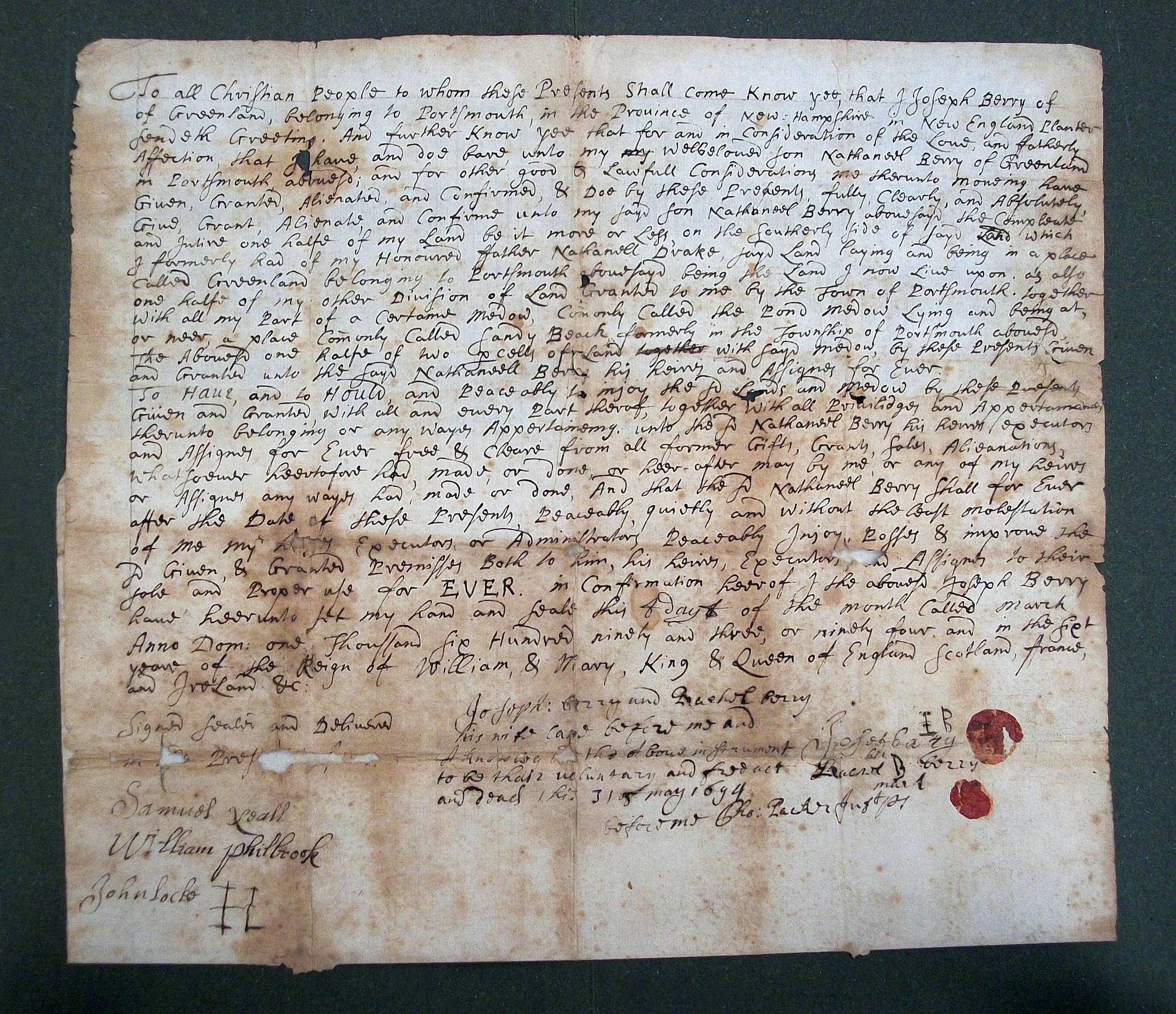

Early on, rules guiding capitalization were largely unknown or unheeded. It was accepted to use a capital letter at the beginning of every sentence and proper name. By the 17th century the practice had extended to titles (Sir), forms of address (Father) and selected categories of nouns. Writers then began to capitalize any noun they felt to be important. The writer of our document not only capitalized selected nouns like "Premises" but extended capitalization beyond nouns to verbs and adverbs like "Given," "Granted," "Peaceably" and most words beginning with a "c". Adding to the complication we see that "ff" was an accepted way of writing a capitalized leading F as ffrance (France).

So while some words appear to have had consistently accepted spellings like "sayd" (said), it was not uncommon for the same word to be spelled in different ways, sometimes even by the same writer within the same document. An example in our document is the name "Nathaniel" shared by Joseph Berry's stepfather and son, which on this single page the document's author wrote as Nathaneel, Nathanell and Nathaneell.

Even those of advanced education were inclined to spell words as they sounded. Our document also contains - "hould" (hold), "welbeloved" (well-beloved), " medow" (meadow) and "wayes" (ways). In the eighth line "Intire" is a capitalized misspelling of "entire". Extra "e" letters were often added as in "doe" (do). Other letters are omitted as in the word "p cells" (parcels) and the "sd" contraction for "sayd" (said). Dr. Packer himself wrote "dead" (deed), "thair" (their) and "Just ps" (Justice of the Peace). The fact that spelling was not yet standardized in the 17th century should not be too surprising in light of the evidence that three of our document's six signers could not write their own names.

Regarding Locke and Berry's authentic initials, "L" and "B" are easily recognized but their "J" initials are not. The explanation begins with the fact that through the 1600's i and j were not universally considered two distinct letters, but different forms of the same letter, hence ioy (joy) and iust (just). The fact that the letter j is dotted is an acknowledgement of j's emergence from the letter i making it one of the last letters added to our alphabet. This explains why many sample alphabets from the early 17th century do not include a distinct j character at all.

The distinct symbol for j and the custom of using i as a vowel and j as a consonant are first found in the 1630s, yet the duality in their usage continued into the 18th century. This i/j duality is illustrated in the first line of our document where it appears the writer made a false start with the J of "Joseph" and then wrote "Joseph" in full. But there was no false start. "I Joseph Berry" was properly written "J Joseph Berry" reflecting the fact that for the writer, the sounds for both I and J were represented using the same character.

The vertical stick symbols written by Locke and Berry for their "J" initials can be found in an obscure Italic form of caligraphy for the letter I. Like the document's author, for them the same character could represent the sound of either I or the emerging letter J. So the initials written IL and IB on the document should be interpreted as JB and JL, the personal marks of Joseph Berry and John Locke.

A number of phrases appear repeatedly in 17th century deeds and official papers. Our document opens with one - "To all Christian People to whom these Presents Shall come". Another common phrase then and still in use today is "in the presence of us" which is the text in our document damaged at a paper fold. But a common phrase no longer seen was

"me therunto moveing" which meant "important to me". But do we really understand the full import of such coloquial phrases?

Consider researchers 350 years in the future transcribing "It is what it is". Will they think it just an inconsequential, duplicitous error or will they somehow grasp the hopeless resignation and surrender to fate we know it is meant to convey? Recognizing words and knowing what was meant can be different things.