On the Mouth of the Piscataqua: Unearthing the Rich History of Odiorne Point

By Hunter Stetz - as originally published in May 2023, and republished with the permission of, the Seacoast Science Center, Rye NH

David Thomson’s relocation to Boston in 1626 was followed by decades of sojourns by various European fishermen and explorers. In 1660, a fisherman named John Odiorne settled the rocky shores of what is now Odiorne Point State Park. To say that the Odiorne family stuck around is an understatement! Sometime in the 1650s, two brothers and their cousin left the coastal village of Sheviock in the Cornwall region of southwestern England, in pursuit of economic opportunities in North America.

Odiorne Family home, built ca. 1800.

John Odiorne and his younger brother, Phillip, first appear in colonial New Hampshire records in 1656 and 1657 respectively. John was recently widowed. Isaiah Odiorne, also of Sheviock and likely a close cousin of Phillip and John, immigrated to Smuttynose Island (Isles of Shoals) sometime in the 1650s or 1660s. All three participated in the fishing industry based out of the Isles of Shoals.

John first owned land on Great Island, now known as the town of New Castle. In 1660, he sold this land, as well as his fishing operation on Smuttynose Island to purchase a tract of land that now constitutes Odiorne Point State Park (also known as Odiorne’s Point). He began building his home here shortly thereafter. Having been widowed shortly before leaving England, John married his second wife, Mary Johnson in 1667. Little is presently known about Mary’s life, but she raised their four children and certainly played a significant role in the farmstead’s daily operations.

Glass chip with “JO” etched in it, identifying it as belonging to John Odiorne.

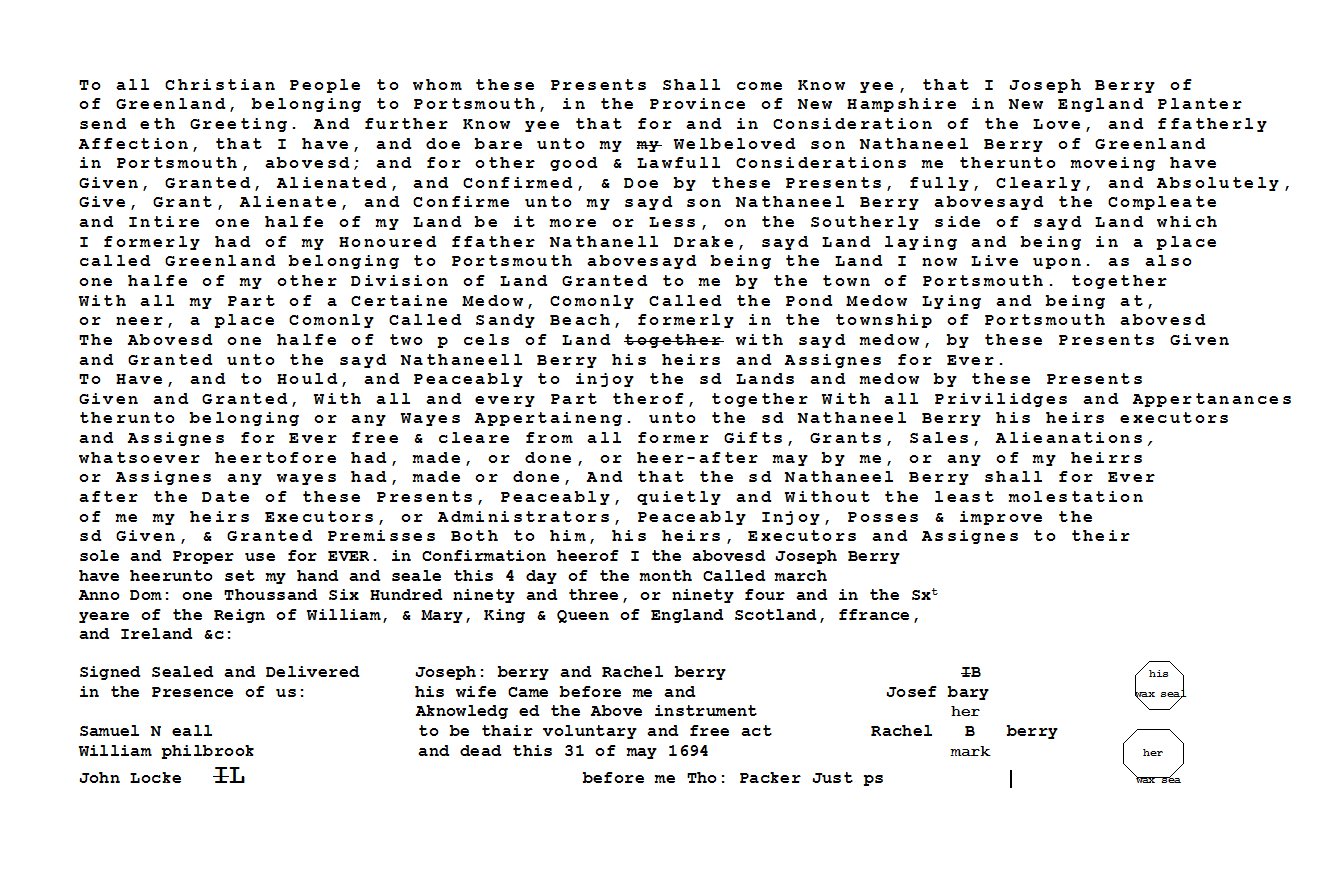

The Odiorne farmstead first fell within the boundaries of Portsmouth in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, but New Hampshire regained its status as a distinct provincial colony in 1679. In 1693, portions of Portsmouth, including the farmstead, separated to form New Castle. It remained part of New Castle until 1791, at which point it was annexed by the relatively new town of Rye. Odiorne’s Point was known as Rendezvous Point until around the time of the American Revolution, at which point it was renamed to honor the Odiorne family’s already lengthy ties to the area

Historic records indicate that the Odiorne family continued to fish once settled at their farmstead. They were also engaged in farming and regional trade with both Indigenous peoples and fellow colonists. A document detailing John’s estate a few years prior to his death describes the farmstead as having a dwelling house, “barns, stables and houses, gardens, orchards, upland meadows, [and] pasture ground.” After he died in 1707, his son, John Jr., inherited the property. However, it is believed that he had already erected his home elsewhere on their land in the decade preceding. Historic records and archaeological evidence suggest that the original house was not occupied after the death of the elder John.

The Old Odiorne Point Burying Ground was likely set aside for burials in the early 18th century, making it one of the oldest European settler-colonist burial grounds in what is now New Hampshire. Most of the graves are marked by uncarved fieldstones, so we do not know exactly who was first buried here and when. However, there are 14 marked graves that date between 1804 and 1865.

The surname “Odiorne” (pronounced “oh-DEE-ahn”) comes from “Hodierne,” which itself derives from “of this day” in Latin. It is speculated the last name arrived in England in the 11th century with Normans from what is now France. Interestingly, the spelling variant we are familiar with only came about when John, Phillip & Isaiah arrived in the New World, meaning that anyone with “Odiorne” in their ancestry can trace back to this early colonial New Hampshire family. The Odiorne Family Association commemorates their roots by meeting at the state park every summer. Because the Odiorne family resided here for about 282 years, later chapters of their ties to the land will be discussed in blog posts later this year!

Odiorne family crest.

Postscript - I am a proud 13th generation descendant of John Odiorne Sr. My direct line owned the farmstead until my 7th great-grandfather, Benjamin Odiorne Jr. died in 1804. However, he probably lived in the second house built by John Odiorne, Jr., which has not been located by archaeologists.

To read more about Odiorne Point visit Seacoast Science Center’s blog page